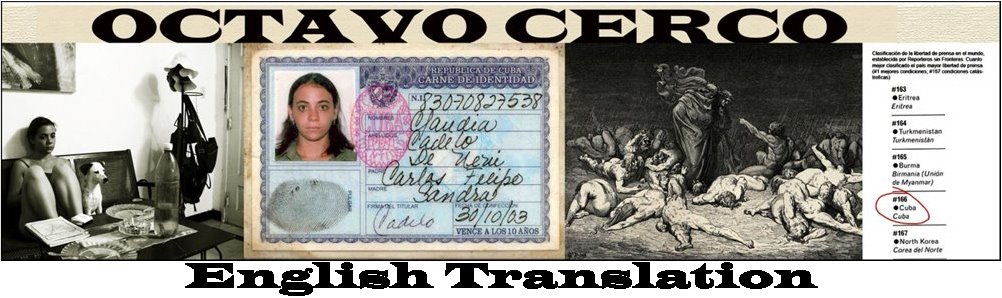

Photo: Truck with old refrigerators in my neighborhood.

Amelia is about 50 and lives alone, her husband died in the war in Angola and since then she’s received a miserable pension through the Veteran’s Association. As she doesn’t work for the State, tough she is still of working age, several times they’ve tried to take from her the pittance of 200 Cuban pesos she receives as “financial aid.”

Since she exchanged her refrigerator for a more energy efficient one, her life has been complicated: she has cold water but owes the state 2,000 pesos in thirty monthly payments, plus late fees, which she hasn’t been able to pay. For some months an “inspector” has visited her house weekly, to tell her of the really bad things that are going to happen in her case. It all started with a fine, which exceeded the unpayable debt itself. As that didn’t work, it moved on to the blackmail of threatening to remove the refrigerator, and finally the threat of a trial.

Amelia knows she can’t raise this sum, and her inspector, gaining confidence as she looked him in the eye, confessed to her that he has not been able to meet his own commitment to pay for his refrigerator, either.

In a bizarre “Year of the Energy Revolution,” an epithet that was written below the date on every official document and on school blackboards during all of 2006, Fidel Castro decided to update our home appliances. The energy itself never came, but our lightbulbs, fans and refrigerators were exchanged for new ones, along with promises that we would pay for them on the installment plan.

Some years later, a rather high percentage of Cubans owe thousands of pesos to the State, Cuban Communist Party meetings demand of their militants that they “ensure compliance with the commitments in their nuclei and their neighborhoods,” and, incidentally, “set an example by settling their own debts.” But after 50 years -- Party member or not -- the common denominator of the average Cuban is insolvency. This bankruptcy of the family economy is the result of government mismanagement, which now demands that we pay what we have never earned.

Outside Havana, Cubans Live an Existence Without Electricity, Exhausted and

Sleepless

-

Many families cook on their porches with coal or firewood and the air

becomes unbreathable due to the smoke. 14ymedio, Mercedes García, Sancti

Spíritus, 29...

5 months ago