Photo: Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

She grabbed the mission for several reasons: they would put 50 Cuban convertible pesos (cuc) in a bank in Cuba every month, she could acquire the home appliances that she’d needed her whole life, she could buy her children clothes, and what’s more, she could leave the damn polyclinic that was ruining her life.

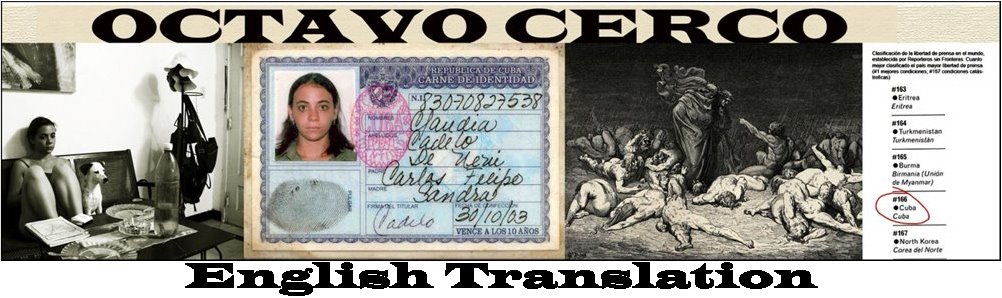

She knew Venezuela was pretty violent and politically unstable, but the Cuban delegation would surely be well protected, supposedly they were a priority. They were located on the outskirts in a poor, high crime area. No one warned her that after she got there they would take her passport and she would be undocumented. She worked hard, discovered that most Venezuelans felt like Cubans: politics had split the society in two.

She suffered the hatred of a people who, like hers, had lost control of their future. She discovered that paranoia knows no borders and that fear also travels on airplanes. A colleague of hers was killed in a brawl between gangs in the neighborhood. She asked to return to Cuba, but the commitment was unbreakable -- like the Communist Party -- and being depressed is not consistent with solidarity among peoples. She still can’t return and to console herself she gives herself therapy in front of the mirror every morning: 50 cuc, 50 cuc, 50 cuc.

Outside Havana, Cubans Live an Existence Without Electricity, Exhausted and

Sleepless

-

Many families cook on their porches with coal or firewood and the air

becomes unbreathable due to the smoke. 14ymedio, Mercedes García, Sancti

Spíritus, 29...

4 months ago