I met Boris by an odd coincidence. One day he came to my house to find some music and we ended up talking about literature. I discovered that we had a world in common: the desire to be free, to know the truth, to dream about another, less battered, Cuba.

He left me this text and I never knew where or how to publish it. “It’s old,” he told me it, “I wrote it when Fariñas ended his hunger strike, but still I want you to read it.”

Boris knows, as I do: Coco carries the history of Cuba on his shoulders. With his martyrdom he is writing the heroic deeds that we have not even been able to dream of.

I offer you this text now because although Guillermo Fariñas has been eating since July, his body still carries the pain of such a long strike. And because there are men and actions that last forever.

"The Responsibility of Guillermo Fariñas" by Boris González Arenas

Less than a week ago I had begun to write an article about Guillermo Fariñas. Just days before, on Saturday July 3, the

Granma newspaper had published an interview with one of Guillermo’s intensive care team. At the end of it made it clear that he was already in serious condition and could die if things didn’t go well for him.

I was unwilling to let his death pass without something more.

Suddenly, yesterday, Friday, the Cuban government made a commitment that within less than four months they would free the rest of a group of Cubans who had been disgracefully arrested years ago and condemned to outrageous sentences. I learned from friends who had read the news that Guillermo Fariñas had abandoned his hunger strike.

My joy could not be greater. The political prisoners will be released and Guillermo Fariñas, who has won the admiration of all for his unswerving commitment, will live.

I envy the feeling a generation -- my children -- will have when they read about this episode where the tenacity of a handful of men and women overcame a huge repressive apparatus and the totalitarian arrogance of its beneficiaries.

No one can read about this episode without a minute's silence for Orlando Zapata Tamayo, whose death we know about not because the Cuban state chose to communicate it, but by the universal indignation of the best of the citizens of the world. A man whose death we also found out about because of a cowardly article published in the official Cuban press, four days later, full of bombastic and disrespectful language that still has not been moderated, despite the fact that everyone is repelled by it.

Is the freedom of those condemned the long-awaited pivot point of the Castro regime, with its decades of failures? Now, in a fit of common sense, has it decided on a slow but irreversible process of change in our country?

I’m sure that’s not the case, that the Castro regime would rather see this nation burn than facilitate its revival from the death it has imposed on it. I want to be wrong, my mistake would be the good fortune of a country that has suffered enough.

Fariñas and Tamayo are symbols of the Cuban resistance and the determination of our country to achieve the social and political freedom that has been so elusive. Both have shattered the perverse policy of presenting the opposition as a handful of men paid by external enemies for chanting what the national and foreign intellectuals have failed to bring to light.

Because is he not tired of the things of life, but only of death, Fariñas is now one of the leaders of the Cuban opposition; his victory has become a foundation of the new Cuba, of a country perpetually under construction. Not of a tiny opposition that aspires to see the entire structure of the Cuban state blown up, and along with it thousands of compatriots in a fratricidal confrontation, but of an opposition of all Cubans who have suffered under decades of the Castro regime’s immobility and irresponsibly and who now demand the reconstruction of our state based on our own free will. Who demand the reconstruction of a Cuba of plural decision-making, one that will not be stopped, by fearful and cruel despots, from the greatness of the task that our citizens have never hesitated to undertake.

Not to build our country to surrender it to the enemies of humanity, whose presence in sovereign nations and whose arms impose an authority over the lives of children, men, women and the elderly. Although today the United States is governed by a progressive leadership no one should forget that in former times it led a genocide and nothing prevents a similar process from overshadowing its present work in a few years.

|

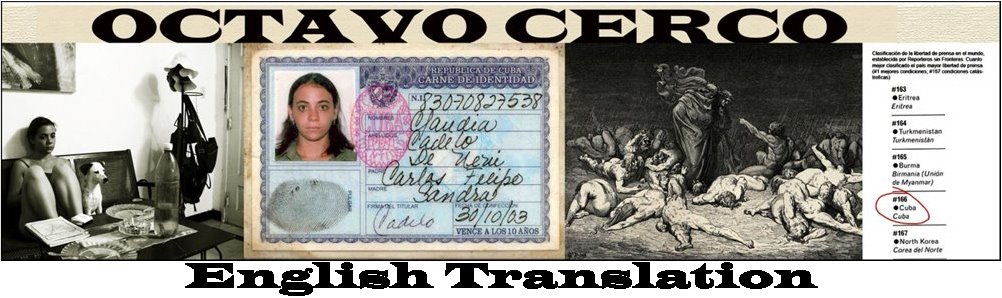

| Guillermo Fariñas and Ciro in March 2010. Photo Claudio Fuentes Madan |

Nor to build our country under the shadow of credits committed by the Latin American political class, inflamed traditionalists whose treacherous background we Cubans know all too well.

The inordinate challenges facing Cuban society are a consequence of the greatness of its mission, and the severity of obstacles presages a prodigious generation of men and women from the whole world coming to the only conceivable conclusion, a full realization of our humanity.

These are times when we must look at Cuba with new eyes, to feel the force of its breath and the strength of its people. The breath and strength of unsuspected resonances and vigorous inspiration. Guillermo Fariñas is the peak of its virtue and the awakening of its hope.

It is not a small thing that he has asked of his deteriorated body, but men and women like him, those who decide to pull the world toward the dawn, cannot falter when they see the first light.

Sunday July 11, 2010