Text: Ernesto Morales

Cuban journalist, living in Bayamo

ernestomorales25@gmail.com

The last images were fade-outs from a plane, a vision of an island parading along the Havana Malecon, and I noticed from that moment that my mood had changed drastically. The National Television News of Monday, March first, did it in one blow. Ten minutes before, I was living my own life and thinking of my own dead. But after seeing the helplessness in the eyes of Reina Luisa Tamayo, an elderly woman of dark skin and simple words, who from that second, I’m sure, still mourns for what a mother should never have to mourn – the death of her son – nothing could be the same as moments before.

If there is anything about the brazen hidden cameras to be grateful for – as they violated every ethical and moral precept, filming this woman during the medical consultation, showing her naïve hopes in those men in the white coats whom she asked to save her son – it is just this: it taught me to know her face. To know her features to confirm what I already knew: this poor woman can not, could never, understand the death of her son Orlando Zapata Tamayo, the prisoner of conscience who, in my sad Cuba, stopped breathing last February 23, after 86 days on a hunger strike. At most, Reina Luisa knows the pain and now, probably the hate. But not much about the ideology or politics.

And she could not understand why the battered body of her son has to be covered with earth. Because not even I, not one civilized being, proud as we are of our species, can understand the death of a 42-year-old Cuban who died gasping, his body lacerated by the force of starvation, in order to claim with an epic bravery and, why not, somewhat orthodox, what from his simplicity he considered his inalienable rights. In short, what we would call a decent prison.

This death make us dizzy. It is disconcerting. This death that did not have to be hurts those of us who believe in the best of humanity, which is not about our ideological postures, but about our feelings.

And it leads me to question, inevitably, this Island that many inhabit with pride, others with sorrow, and others with the certainty that it all belongs to them. I think of civilized barbarity, and of how in the name of supposedly righteous causes, a Government can bring out the worst in those it governs: dehumanizing them.

Someone told me recently: we have a sick country. And I say: Yes, sick of apathy, of resentment, of degrading feelings. A country cannot be healthy where National Television shows on prime time news such ignominious material, and where after millions and millions of eyes see it, and millions of brains process it, it does not generate protests, nor even significant movements that question the event. That ask for real justifications for what is not said, for what it purposefully hidden.

I think: the author of such material, the journalist who lent her intellect to such infamy, lives in our country, certainly has a family, perhaps children. This journalist is miserably sick of lies.

Was it a repeated error, every time it was aired on several news programs, that its author was apparently not credited? Or did the same person decide, as a last minute precaution, to hide her identify behind an off-screen voice? Many identified her, assumed her well-known television presenter’s name, but she, suspiciously, preferred to hide it. I wonder how someone whose creed should be truth, someone whose watchword should be “objectivity,” can sleep at night after handling in this way a case that should provoke in all of us, at the very least, a wave of shame.

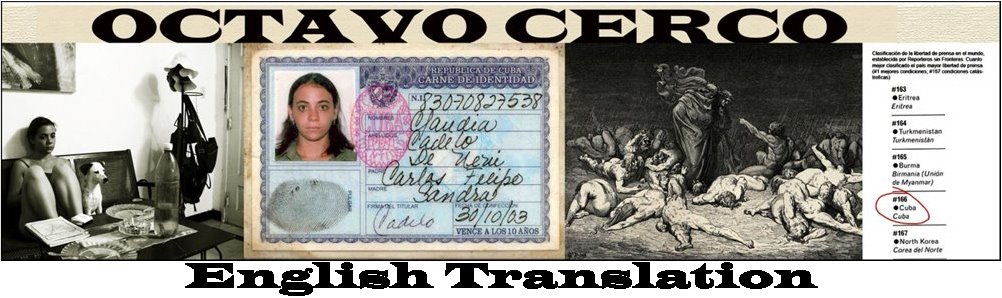

Orlando Zapata Tamayo was arrested during the infamous Black Spring. He did not figure among the commonly broadcast names of the 75 independent journalists imprisoned, because instead of a thinker, journalist or intellectual he worked as a humble bricklayer who engaged with frank radicalism in his labor of opposition, and who was sentenced initially for three years privation of liberty as a result of his public demonstrations against this wave of arrests in 2003.

Once behind bars, however, this sentence was increased to a staggering 25 years for disrespecting the authorities, terminology which in practice meant refusing to wear the inmate uniform and to be treated like a common prisoner. Since then, the former worker, born in Banes in the municipality of Holguín, figured as one of the recalcitrant "counterrevolutionaries," who refused to be treated as common criminal, and who maintained his intractable attitude to those who sought to bend him by force.

That was the genesis of the tragedy. Rather, its first act. The second and decisive act opened in December 2009, when Orlando Zapata formally declared a hunger strike.

What motivated this prisoner with his voluntary fast? The report on Cuban television said, coldly and contemptuously, that he wanted “a TV, a kitchen, and a telephone in his cell.” According to the words of his mother, what he fasted for was, “to have the same living conditions that Fidel Castro had when he was Fulgencio Batista’s political prisoner, The same living conditions of the five Cubans imprisoned in the United States.”

Perhaps Orland Zapata did not think that his resolution would send him headlong to death. But what I am sure of is that the authorities of Kilo 8 (the prison in Camagüey where he was being held) never imagined the stony determination of his position. Even as it cost him his life.

A story that does not explain causes cannot call itself journalism. The material exhibited on our television was dedicated to “dismantling” the argument that Zapata Tamayo was not seen by doctors when his condition required it. Nothing more. It was never explained to the millions of viewers how it was possible that the arrogance of a prison system would allow the progressive debilitation of a young man who was not asking for the impossible.

The question is not, “What did the Camagüey doctors do to try to restore life to a body desiccated by hunger?” We assume: a doctor who sits at the heart of the sacred should save lives, could not have done otherwise than to fight tooth and nail against a death that had already won every fight. The question is: “How is it possible that the doctors so unflinchingly ignored the claims of a prisoner whose crime was to think differently, so that from the moment he went into the hospital his deterioration made any attempt to save him futile?” Is it that Orlando Zapata Tamayo chose a slow and horrendous suicide? Is it that he didn’t love his life? Was it irresponsible, as they try to make us see on Cuban Television, that he didn’t measure the reach of his actions, that he did not feel the martyrdom of his hungry body?

I refuse to accept it. Orlando Zapata, a Cuban whom I never met, whose ideas, principles or human values I do not know, whose conduct I cannot even assess objectively due to the disinformation and manipulation to which the official press of my country condemns these issues, Orlando Zapata had the courage, which in “Cuban” translates as “he had the balls,” to live consistent with his ideas. He knew how to do what so many worn out slogans and so many phrases from the podium cannot encompass with their rhetoric: give his life for a cause.

The television report should be stored in our minds. When a person who knows how to build a better country remembers this, the example will teach us how far we can go. How far? Even to publicly showing the hidden camera films of this desperate woman, who was grateful for every word of encouragement that would give her back her faith in the life of her son, and whose words (or those they tried to make her words) would be aired without the least respect for her integrity, her rights, her pain. To present, one more time, private telephone conversations, taped in a zealous spying process too similar to the one the official Cuban press criticized George W. Bush for, with the difference that at least the intelligence service of the nefarious president hid those recordings. They did not air them on prime time television in the United States.

Can they stoop any lower? They can: behind the photo of Orlando Zapata shown on the screen, an image of an evil frown zealously chosen to present to the Cuban public, the author of the material contrasted it with one of those marches of the multitudes Cubans know so well. Those million Havanans who slithered along the Malecon, in the visual language of this report, strongly disputed Zapata Tamayo. They disputed him, according to the exact words of that ethereal voice-over, with fists high, in response to his blackmail and provocations.

Not a single opposing opinion. Not one argument to the contrary. Not one witness to the living conditions of this prisoner of conscience and what led to his fatal protest. That is, Orlando Zapata was not a “plant” who refused to accept the status of a common criminal and demanded his rights. No. Orlando Zapata was a victim of those who infected him with this idea of rebellion, of the degenerate counterrevolutionaries who pushed him to his death. It’s that simple.

For these captors of the truth, the principle of disagreement with their ideas is a concept so vague, so lacking, that only in this way can they understand that a 42-year-old Cuban would paralyze his stomach to claim the right to be treated with respect. Only in this way: like an irresponsible person. A naïve person exploited by the real enemy

Once again, as Eduardo Galeano would say: Cuba hurts.

We grieve for those who don’t accept that things like this are possible, that deaths like this happen, that suffering like this takes place under our noses. We grieve for those who believe that instead of burying people with different opinions, now is the time to disinter their ideas and build, with all of them, the clever and the crazy, the shrewd and the obvious, a more plural and tolerant nation.

And it should pain everyone who thinks of Marti, a prisoner at sixteen, a victim of abuse and cruelty, for being a political opponent. It should pain everyone who thinks of Mandela, imprisoned for 28 colossal years for opposing the ideas of an exclusionary system. Yes, for being an opponent. It should be felt in the flesh of every decent Cuban, because one more of us, one of those born under the same sun, who built houses with his hands, who suffered shortages and laughed out loud, who drank rum once in a while, perhaps, and who dreamed of a country other than that imposed on him, who died a death that never should have been.

If our flag wasn’t sold for hard currency in this tropical Cuba, and in consequence, if each one of us would raise it somewhere in our homes, raise it to half-staff (although this was not a leader nor a famous man) it would be a just way to maintain a dignified silence before the death of this unknown man. It would be a way to preserve our last wealth: human dignity.

And against that, no ill-fated reporting can do anything.

Note: I read this article for the first time along with the interview that Ernesto conducted with Yoani and Reinaldo. I had never met him but his texts make me feel like I’ve known him my whole life. Sign here for Freedom for the Political Prisoners of Conscience.