|

| "I'm a worm*. I'm popular." [*Fidel's term for Cubans who leave Cuba.] |

I met her in 2004, we had a mutual acquaintance, a neighbor of mine. She spent her life in clubs and at concerts, always with boys who came to collect her in a car. I liked her, she was fun. In the afternoons when she woke up sometimes she’d come and have coffee at my house. With her parents abroad, she lived without working and even though she was sometimes short of money, her nights out weren’t affected because the men paid.

Chance, that had one day put us in the same neighborhood, separated us. For years I didn’t hear from her and thought, as is common on this island, that she’d left the country. Recently we ran into each other and I discovered I was right, she lives in New York now and comes to Cuba on vacation. I don’t know what happened, Cubans find so many ways to run away from this land that I don’t even take the trouble to inquire, though the stories can be funny, but also very sad and sinister. Also, I’m a little sensitive on the topic of emigration, wondering who will be here beside me in ten years, when all my friends have left.

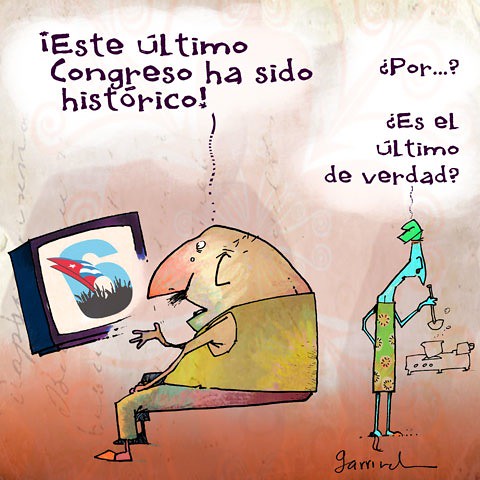

In the short time we shared, she told me that she worked a great deal over there, and that generally speaking, she’s considered a communist. “Communist?” I exclaimed, “You were a big fat worm. What happened to you?”

“The system in the United States,” she said, “is inhumane, here it’s better, more humane.”

I looked at her with my mouth hanging open. She doesn’t like the new country where she lives because she has to work; in Cuba she didn’t have to because she was a kept woman. How can you use politics to justify your own inability to be productive?

“I don’t agree with you,” I said, trying to contain the passion that comes over me when people come from a democracy and tell me fairy tales about the dictatorship. “Sure, a lot of people don’t work because the salary is ‘inhumane’ and no one is interested in breaking their back for nothing. But still it seems very good to me that you have to work to earn your own bread. It’s normal.”

“Cubans don’t like to work,” she replied, and then I knew that because she didn’t want to work she assumed everyone else didn’t want to either. What a capacity for generalization!

Before we parted she told me she was about to have an operation. I assumed it would be in Cuba, given what a humane government we have. You can’t even imagine my surprise when she exclaimed, “No! I’m having it over there!”