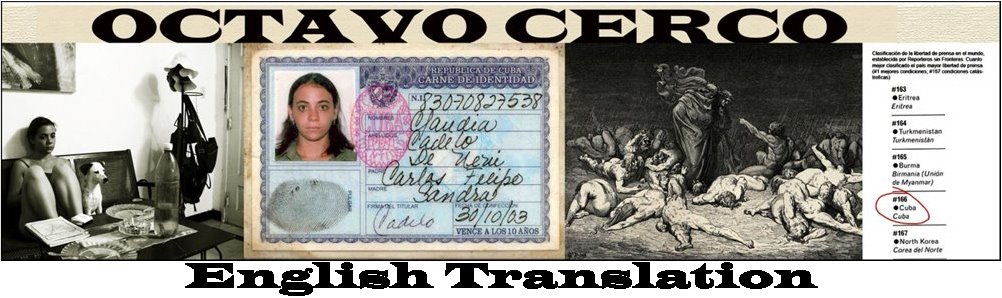

Foto: Claudia Cadelo

Foto: Claudia CadeloTexto: Claudio Fuentes Madan

I would much rather consider the events that took place than to just describe them and to talk a little about the reasons that brought us to the attempt. While at Claudia Cadelo’s house for more or less a week now, I find myself faced with her worry about the Antúnez situation. She was torn by a mix of contradictory assessments and battling clashing feelings.

She would comment to me about the points or statutes that this gentleman defends and demands of the Cuban government in a hunger strike he himself started a little over a month ago, according to what little information we had on the subject.

Claudia would tell me that the news about the dire state of his health was not moving anyone, or very few, and that, in addition, she considered it somewhat ghoulish that if anything happened to Porno Para Ricardo or to

Yoani Sanchez, for example, then no doubt a big media fuss would ensue, but in the case of Antúnez, nothing of the kind was happening.

I remember that we reached an agreement of ideas in the things we talked about: the different people who hope for and attempt changes in Cuba, those who question the laws and measures of the fifty-year-old government, those who, on great many occasions, have been on the receiving end of every kind of repression, harassment and violation of their most basic civil rights. We don’t think alike in our analyses of methods and ways when facing the same situation of aberrant deficiencies in which the majority finds itself.

But along with the disagreements over chosen strategies, there exists a magnificent concurrent point: we all want the whole range of historically known freedoms, which I won’t talk about, and each day, not only outside Cuba, but from the very entrails of the sparsely bearded one there are more who confront them, out of personal courage, even, of course, at the risk of errors that will take place along the way.

Claudia would look at me and would repeat that no one was doing anything, that even she wasn’t doing anything. In a certain way, I was deep in a similar situation, so, in order to eliminate that strange feeling of absence, in which I knew very well that we were all part of this mass now called by Claudia, NO ONE, I blurted out pretending I didn’t mean it: why don’t we go there, straight to the source of the problem, along the way we can visit Placetas, soak it up first hand, we could talk to Antúnez, discuss our points of view, etc., we can interview him. I was remembering a fantastic article by Reinaldo Escobar tilted, if I remember correctly, “the problem, my problem,” that I read in his blog

Desde Aquí. Claudia suddenly stopped hyperventilating, she became calm and, without blinking, she agreed.

Four days later

Ciro Javier Díaz and this writer left for Placetas, having paid for the tickets with our own money and the taste of a break from our daily routines with the damn adventure. Barely 20 minutes after our arrival, at around 11 A.M. on Monday, March 23rd, 2009, a few meters from the supposed corner of Antúnez’s house, a patrol car met us with that certain usual violence in these cases, taking us to the police station for the usual interrogations. We were freed the next day, March 24th, when they put us in a car and took us to the Havana bus terminal without charges, accusations, or further explanations, returning our personal belongings: my cameras, bags, identification cards and even some CDs of Porno Para Ricardo and La Babosa Azul that Ciro was carrying to give to Antúnez as presents.

And now, comrades, for a climax, the list of violations that the repressors in this trivial and not-so-tragic-in-appearance case have committed in the exercise of their full-time routines:

1 – The inability to roam freely in any zone or region of the national and sovereign territory. It’s clear, then, that the nation is only enjoyed, embraced by its controllers, and our experience reaffirms the suspicions that citizens without government duties or related to it are confined to a ever increasingly precise and limited region.

2 – We were deprived of the right to make a phone call while detained. When we asked if this was possible, the official in charge inquired what was the objective of our request, if we intended to inform our family and friends about our situation. On hearing the logical and affirmative answer from our own throats, he started to laugh sarcastically and asked us how we came up with such an idea, that we’d be leaving soon… we left the next day. At least we did not have to pay for the return ticket; that turned out to be the responsibility of the Security of this Shameless State of Siege.

3 – They crushed the simple right and freedom to assemble with whomever we wish, the civil right to freely get information through whichever means we feel like, and the power to later disseminate our views about this, although this last one turns out to be more shocking, furious and difficult every time. The little Internet that we manage to scrounge will also serve to denounce them and to express ourselves.

4 – Hours after having had my cameras returned, I realized that they had erased the photos contained in one of them, the compact digital. The images in it could be easily seen on its screen and were personal images and memories that had nothing to do with what happened. I understand that this is the obligatory and violating modus operandi in these cases, which shows that they have a terrible fear of the investigations by common citizens, where it’s clear that it’s the controllers who have to hide their barbaric actions, and who fly into a rage behind the backing of an abusive authority at any attempt at real journalism.

Nevertheless, I want to make it clear to them that we didn’t expect any other action on their part, always with their ritual of abuse and manipulation. We understand that they do not have the option of other methods, always the same and dogmatic ones. I really understand and commiserate, with and without irony, that they should act from the same cage of conduct. It’s the only way they can maintain their ambitious and powerful predatory behavior, increasingly weaker and lacking in arguments, so I hope they will also forgive me if I subtly shit on their guts and toast to them, besides, my most sincere pity for contributing and carrying such a painful burden of evil.

PS – It’s already Thursday and it’s now that I’m finishing this writing, not only because of a slight, real and habitual laziness that generally accompanies my intellectual activities, but also because, on top of everything else, when I started these lines yesterday, Wednesday the 25th, I found out that Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo had a summons for 3 P.M. at the Lawton police station. Waiting outside were his girlfriend, and Claudia and Lia, so I decided to join the fat bastion. He came out at around eight P.M. in a state of an indescribable emotions, and together, all of us decided to continue the evening, analyzing this new instance of violation.

It may seem odd to you, but I continue to enjoy that strange living life to the fullest of everything that is happening, and I pride myself on having at my side people from whom I learn while enjoying them immensely from the silence that always remains with me while I laugh about some thing.

I remember other speeches:

I remember other speeches: