On Saturday morning I get a text message from a girlfriend, “Claudia, I’ve refilled your phone.” The way the service operates, I should expect another text message from the Cuban company. It finally arrived at 9 AM Monday, and said the following:

“From RECARGA1: Call (7) 204 31 45 between 8 AM and 5 PM from a land line to confirm data regarding a refill received through the Internet. If there are problems with the payment, the service will be canceled.”

Can someone please explain the second sentence to me?

After nearly an hour calling without being put through to the telephone indicated on my cell, a girl answers at the other end of the line, sounding as far away as if she had said, “Hello,” from China. She asks me my number, asks who paid the money, and I tell her the name of my girlfriend. She says it had been a man, and I can’t collect until I have the details of the person who made the transfer.

I complain, on the

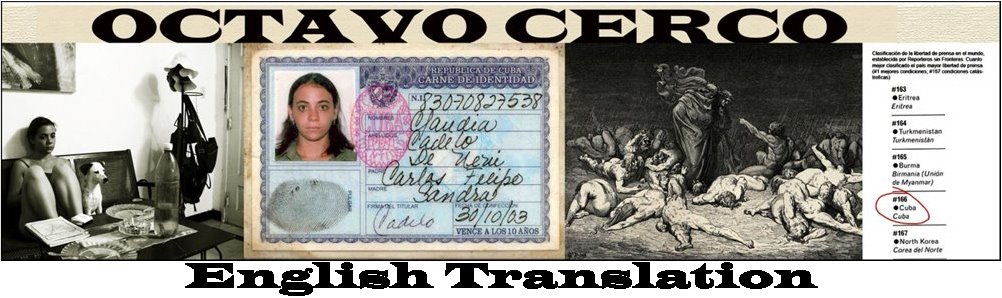

web page where the service is promoted it doesn’t indicate this fundamental detail. With the apathy characteristic of a Cuban receptionist, she says, “Your suggestion has been noted.” And in passing, she asks for my identity card number.

It turns out I’ve received two refills on my cell phone: the first, that of my girlfriend, they never warned me about; on the second – surely some reader supporting this blog – I can’t collect a single centavo. And so it goes in technological Cuba…

Note: When later I logged onto the Internet I could not enter the site to refill cell phones, with the strange justification:

Forbidden. You do not have permission to access this server. But because I am stubborn, I went in through a proxy to verify that nowhere is it stated that the user must inform the Cuban that a refill has been made to their phone.

The most secure way to refill cell phones is

TuRecarga.