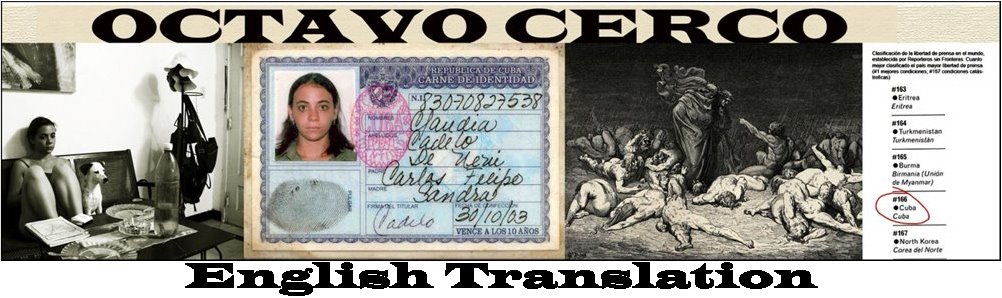

Photo: Claudio Fuentes Madan

Lately I’ve talked with some journalists who tell me that people are talking about a new Special Period*. Fortunately it doesn’t get to me to hear those frightening comments, but I do remember some details of what was for me, in my mind as a child of six, the apocalypse.

The first time I heard these two words was in elementary school while waiting for the cookies and soft drink during recess when a friend announced with desperation that, “We will never have snack again.” With tragic face—I was a little fatty at that time and the news hit me as fatal—I shot back, “Why?” typical for my age. And the answer, also typical, didn’t tell me very much, “We are in the Special Period.”

For some months “Special Period” was, for me, the fast between breakfast and lunch. With time, I broadened the concept a little: not having shoes, not having enough to eat, seeing my house self-destruct and my mother and father desperate, this last was the strangest of all. In those years both were military and I never heard them make reactionary comments. They stoically endured and the only thing they didn’t manage to hide from me was the talk of “Option Zero.”

Time passed and 1994 arrived, even more confusing. The common explanation for seeing ten rafts pass by my house every day was typical: some counterrevolutionaries. The video of the disturbances on the Malecon which I saw when I was 11 at my aunt and uncle’s house, while everyone gave their opinions—everyone was in the Party—told me something happened in those streets that no one was talking about. I don’t know why they let me see it, I suppose they didn’t imagine I would be able to read between the lines.

At that time the dollar was legalized but it was two years before I would see one come into my home. In elementary school I was relegated to a new class but for me there was no end to the “Special Period.” The children bought ice cream in a foreign currency store next to the school and some parents sold candy in the entryway. One day I went home and told my mother:

- Mommy, give me money to buy an ice cream at recess.

- I don’t have money.

- Don’t be a liar, you work from eight in the morning to seven at night. You do too have money, that you don’t want to give me.

My mother didn’t say anything in response at the time, although later she prepared a little speech in which she explained the idea of “a salary in national money”; at that time the dollar was at 120. Some days later she told me I said:

- Mommy, I know what you have to do to make money: you have to sell candy at the entrance to the school.

When people ask me if I have want to have children, it is this type of mother-child dialog that comes to mind and that, without a doubt, I want to avoid.

Note: Aldo, of the Aldeanos, has been released. They threatened him but in the end returned his computer and let him go without charges.

No comments:

Post a Comment